(Note: The following post was written on May 15, 2022. I later added some paragraphs to clarify my points or address reader objections. You can read the original version of this post here. The most recent update was on May 18, 2022 at 11:22 am.)

There was a thread in a comics history Facebook group last week that I found interesting because to me it was an example of "buying into the myth" when it comes to Stan Lee's claims about Marvel's unique qualities and its success compared to its competitors in the 1960s. Even though everyone accepts that Lee was a constant salesman and self-promoter (which is often cited as one of his strengths by his many fans) it's mystifying to me that so many accept what Lee claimed even in cases where the facts suggest otherwise.

I don't want to pick on the Facebook poster that prompted this blog post since at least he seemed sincere and well-meaning. But here's what happened...

Comics historian Bob Beerbohm started a thread pointing out that Marvel didn't begin to overtake DC in sales until 1972, when the cover price (and page count) of DC titles was raised to 25 cents while Marvel stayed at the lower page count for 20 cents. (It should be noted that sales were generally in decline for most magazines in the 1970s. While Marvel's sales had increased during the late 1960s, their gains did not approach the numbers of DC's former heights.)

Anyway, this fact is at odds with the conventional fan wisdom (but false belief) that Marvel was outselling DC during the 1960s. The fan mentality is that since Marvel had some creative momentum in the early-to-mid 1960s with the introduction of new characters like Spidey and Hulk, this surely meant that they were beating DC in sales. This myth even appeared in a Hollywood Reporter article in 2017 which claimed "the once-struggling Marvel did surprise the comic book industry when it began outselling DC in the mid-1960s, thanks in large part to the colorful, interconnected universe of characters such as Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, The Avengers and X-Men." But comic book sales in the 1960s had little to do with what collectors and fandom (which was dominated by Marvel fans by the 1970s) cared about. So, the facts contradict the fannish assumption that Marvel was besting DC sales-wise during the Silver Age, despite Lee's boasts early on about the "Marvel Age of Comics" and taking the world by storm.

See, for example, page 73 of Lee's book Origins of Marvel Comics, where he writes "As each succeeding issue of The Fantastic Four increased in sales and in popularity, we felt it behooved us no longer to deny a breathlessly waiting mankind the indescribable pleasure of another mighty Marvel superhero." On its face, such a sentence is not meant to be taken seriously, just Lee exaggerating for humorous effect. In this way, Lee was able to make a claim about the extent of Marvel's popularity without its substance being questioned or scrutinized because he's obviously just kidding around. The problem is that many of Lee's readers took his claims seriously, and then have continued to repeat them to others with a straight face. It happened in the 1960s when the comics were coming out, as many young fans became "faithful" Marvelites, urged on by Lee's partisan cheerleading, and then entered the industry as professionals or prominent fans in the decades that followed, helping to promulgate the notion of 1960s Marvel as the gold standard in comics. As other companies (including DC) tried to emulate Marvel in later decades, catering to the interests of the obsessive fan market, the industry was remade in Marvel's image -- arguably to its detriment.

One person who replied to Bob's Facebook post wrote the following: "I was always a Marvel collector. Not sure why DC didn’t appeal to me. Even when I reached the stage where I was collecting books for the art, Marvel seemed to have the artists I liked. I felt Superman was stale artistically compared to what was going on with Spiderman. You had Curt Swan on Supes (I have the greatest respect for Curt) and Romita, Kane doing Spidey. There’s a big difference as far as impact of the art goes."

There are a few things to examine in the above quote. Firstly, the poster asserts that he was "always a Marvel collector," but is "not sure" why he preferred them to Marvel. Perhaps it was the art, he says, which ignores the fact that many artists worked for both publishers. His "Romita, Kane doing Spidey" comment suggests that he is referring to the late 1960s or early 1970s -- a small window in time. (Romita drew Amazing Spider-Man, off and on, from 1966 to 1973. Gil Kane's tenure on ASM was much shorter, off and on from 1970 to 1973.) During that same period, Jim Mooney was often inking the series. Romita's successor on ASM was Ross Andru, who drew the series from 1973 to 1978. All four of these artists came to Marvel from DC: Romita had drawn for their romance line, Kane was the main Green Lantern and Atom artist, Mooney was the main Supergirl artist (for her backup strip in Action Comics) and Andru was the main Wonder Woman artist.

One could argue that their art was better at Marvel than it had been at DC. And of course their art evolved over the years regardless of whether it was for Marvel or DC, possibly even influenced by the reduction in size of original art pages in the late 1960s. But for one to argue that "Marvel seemed to have the artists I liked," and to cite Gil Kane as an example of this, is a bit odd given that Kane is better known for his DC work than his Marvel work. It would be like citing Neal Adams as a Marvel artist and ignoring his work at DC. (Of course it should be acknowledged that both Romita and Kane drew numerous covers for Marvel in the 1970s, even when they didn't draw the inside pages. Just like how Neal Adams drew numerous covers for DC even when he didn't draw the comic inside.)

"I felt Superman was stale artistically compared to what was going on with Spiderman. You had Curt Swan on Supes (I have the greatest respect for Curt)..." This was another common sentiment within fandom back then, where on the one hand they have "the greatest respect" for Curt Swan, and on the other hand they would rather have someone else drawing the comic, perhaps a more dynamic fan-favorite artist like Neal Adams (who, incidentally, was often drawing the covers).

"You had Curt Swan on Supes (I have the greatest respect for Curt) and Romita, Kane doing Spidey. There’s a big difference as far as impact of the art goes." Let's contemplate that thought... "There's a big difference as far as impact" when it comes to Curt Swan vs. John Romita. Really? (You can compare the two artists right here. The Amazing Spider-Man cover shown above is #87 from 1970, drawn by Romita. The Superman cover is #201 from 1967, penciled by Swan and inked by George Klein.)

If we are talking about the 1969-1973 period, which the above comment about "Romita, Kane doing Spidey" indicates, one might recall that Curt Swan's pencils were being teamed with Murphy Anderson's inks around this time, and the results were not "stale artistically" as the poster describes. The regular inker (of penciler Bob Brown) on Superboy in 1969 was Wally Wood, one of the all-time greats. And of course the artist on Superman's Pal, Jimmy Olsen in 1970 to 1972 was Jack Kirby. These facts suggest that the poster is being selective or misleading by implying that Marvel employed superior artists. But what is the purpose of championing Marvel over DC in this manner (when they shared many of the same artists) and how did he come to hold such views?

The poster continued to explain his preference for Marvel: "I saw DC as being dogmatic in their presentation of heroes. All the heroes had to fit into a mold. Marvel seemed more diverse."

It's a bit unclear what "mold" the poster is referring to here, since DC's heroes changed over time. Even Superman changed, if one compares an early 1960s Superman comic with an early 1970s Superman comic (when, for example, Denny O'Neil was writing the comic, and Clark Kent was a TV newsman for WGBS). Batman's evolution throughout the 1960s is well-documented, changing direction in 1964 and yet again in 1969. Wonder Woman ditched her traditional superhero identity entirely in 1968 and wouldn't wear her familiar costume again until 1972. And those three characters -- Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman -- are DC's three most famous superheroes. "Marvel seemed more diverse" than that? When Marvel didn't even publish a female superhero series (like Wonder Woman) during the 1960s?

The poster then wrote: "Of course Marvel was getting into teenagers’ heads with teenage characters like Peter Parker. That was something DC didn’t do."

This comment was the kicker for me, because it was so obviously untrue. I wrote a one-sentence reply: "DC published more teenage-age superhero characters than Marvel ever did in the 1960s and 1970s."

I could have elaborated, but didn't. However, the more that I thought about it, I wondered how the poster could have ever thought such a thing. Was he really unaware of Superboy, Supergirl, Robin (and the rest of the Teen Titans), the Legion of Super-Heroes, Hawk & Dove, Kamandi, etc.?

In trying to figure out an explanation for this, it occurred to me that perhaps such fans are simply parroting Lee's hype about Marvel, how their comics were reaching the youth in college, when the evidence for such an impact is primarily anecdotal -- and mainly coming from Lee. In this way Lee was able to flatter his young impressionable readers that their decision to read a Marvel comic distinguished them from other comic book readers. The tactic can be traced to the debut of Amazing Adult Fantasy in late 1961, which was billed on its covers as "The Magazine That Respects Your Intelligence" despite its simple-minded five-page fare. Its first letters page appeared in issue #12 (May 1962) which contains (as its GCD entry describes it) a "letter from 'John Doe' supposedly an anonymous 16-year old from Texas [who] asks if he broke the law by buying the book. This may be a planted letter by Lee to explain that Amazing Adult Fantasy is a title that can be read by all ages."

Lee's response to the letter deserves to be repeated here, to demonstrate his method of bashing the competition as he praises his own efforts: "No, seriously, the only reason we put the word ADULT on the cover, is to distinguish our carefully-edited, and literately-written mag from the usual crop of comics which seem to be slanted for the average 6 year old with a 3 year old mentality! Anyone with brains enough to appreciate Amazing Adult Fantasy is our type of reader."

A letter in the next issue (signed by one "B. Franklin") complimented the comic in this way: "Do you want to know what I like best about Amazing? It's the fact that the stories are DIFFERENT from all your so-called competitors! Even when you write a clinker, it's still better than any other mag because it's done in a refreshingly different, mature style. It's the one comic I'm not embarrassed to be seen reading in public. And my teacher agrees with me." It's possible that this letter was also a manufactured letter, like the one immediately above it on the same page that was written by one "Joan Boorcock, Newcastle, England." (Boorcock was the maiden name of Lee's British-born wife Joan.)

Eventually Lee was able to receive genuine letters expressing similar sentiments without having to manufacture them himself, as readers followed the template that was set before them in the letters page of what other people were saying and how they were saying it. (Lee noted near the end of this video that he finally began getting the kinds of letters he wanted after changing the readers' "Dear Editor" introductions to the chummier "Dear Stan.") The final "Adult" issue of AAF (#14, July 1962) featured many more letters than the previous two issues, including one from a self-described UCLA English Major who says that the only "fella who tops you [Lee] was named Wm. Shakespeare! But in my book, you haven't any OTHER competition!" Another reader claims "For the first time I've found a comic mag which I'm proud to be seen carrying in public!" (It should be understood that the covers at this time featured such alien-monster tales as "The Terror of Tim Boo Ba!" and "The Coming of the Krills!")

When Lee would later recount the origin of Spider-Man (who first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15, the word "adult" having been dropped from the series title), he would often portray Marvel's then-publisher Martin Goodman as being astonished at Lee's proposal of a teenage superhero, saying that teenagers could only be sidekicks not the hero. Again, this is a baffling claim given that Superboy had been starring in two DC comics (Adventure Comics and his own series) since the late 1940s. Also, one must ignore the teenage superheroes of the past like Captain Marvel, Jr., Golden Lad and even Marvel's own Marvel Boy of the 1950s.

It could be argued that Marvel's innovation was introducing a teenage hero who nonetheless was called "Spider-Man" instead of "Spider-Boy" or "Spider-Lad." And also that, unlike Superboy and Supergirl, this teenage Spider-Man was not a spin-off of an adult character. Billy Batson was a teenager who turned into an adult superhero called Captain Marvel, and Archie's The Fly (which debuted in 1959) was about a teenager named Tommy Troy who turned into an adult superhero called The Fly when rubbing a magic ring. The teenage Peter Parker turned into a "-Man" simply by wearing a costume and presenting himself as an adult rather than what he was, a nerdy high school student. (When the core concept is put into plain words like that, the absurdity of the strip is made more obvious. But according to fandom's conventional wisdom, DC was "silly" and juvenile, while Marvel was "serious" and grown-up.)

So why create a teenage character who calls himself "Man" instead of "Boy"? The explanation is understandable if "Spider-Man" originated with Jack Kirby presenting to Lee the idea of "Spiderman," recycled from Joe Simon's Silver Spider idea that later evolved into The Fly. The rejected "Spiderman" name is already attached to the teenager who magically transforms into an adult hero (which explains the "man" in his name). For that idea to proceed into production, making it onto penciled pages that are then shown to its prospective inker (Steve Ditko) causes one to wonder about how light was Lee's creative involvement in the early stages of not only this aborted version of the character, but in what actually got published in the years that followed. Lee's hand seems heavier after the fact -- after the pages have been penciled, after the characters have been conceived and are expressing their personalities on the penciled pages -- than it is early on, when a blank white page is staring the "illustrator" in the face and the heavy lifting of creation must be done.

But, in the gospel according to Lee, it was he who came up with the name and the concept and had to convince and outwit his own publisher to allow this (successful in retrospect) character to be given life. In the telling of the tale, Lee looks like a visionary and Martin Goodman looks like a dope. This is a common Lee tactic, where he is the lovable hero of the story ("our fearless leader"), having to put up with the resistance of his unimaginative boss, and the quirks of artists like Kirby and Ditko, who seem to hold a grudge against his charming self for some mysterious reason. Before fandom even considered the Marvel superhero line to be the best thing since sliced bread, it was Lee who promoted that view through hyperbole and hype. Eventually fans came around to thinking Marvel comics as "masterpieces," just like Lee said.

But, in the gospel according to Lee, it was he who came up with the name and the concept and had to convince and outwit his own publisher to allow this (successful in retrospect) character to be given life. In the telling of the tale, Lee looks like a visionary and Martin Goodman looks like a dope. This is a common Lee tactic, where he is the lovable hero of the story ("our fearless leader"), having to put up with the resistance of his unimaginative boss, and the quirks of artists like Kirby and Ditko, who seem to hold a grudge against his charming self for some mysterious reason. Before fandom even considered the Marvel superhero line to be the best thing since sliced bread, it was Lee who promoted that view through hyperbole and hype. Eventually fans came around to thinking Marvel comics as "masterpieces," just like Lee said.

A letter in Fantasy Masterpieces #10 (Aug. 1967) offers an example of how the fans began to sound like Stan himself: "After all, who but Mighty Marvel could have dreamed up..." "who says this isn't the Merry Marcher's age of redundant puns?" "I'll just toss a big 'hang loose' at you..." etc., etc. Lee's talent was in giving the Marvel titles a breezy tone that many readers evidently embraced so fully that this Lee voice became their own, and was fed back to him in a kind of shared language. The writers that followed Lee like Roy Thomas came out of this group which became a self-perpetuating factory of Stan soundalikes. Maybe that's why they love him so much; he gave them their voice and made them want to be like him.

Lee's book Origins of Marvel Comics rewrote comics history so that "nothing much was happening" until The Fantastic Four made the scene in 1961. Fans who didn't know any better (and some who should have) internalized this distorted view of what was going on in the comics industry in 1961, and the rest of that decade. Even Alan Moore, in an interview published in the Dec. 1985 issue of Mile High Futures, was quoted saying the following: "If Fantastic Four #1 hadn't come out when it did, then the comics field would probably have died a lot sooner because DC was stagnant at that time and the readership was falling, slowly but surely. It wasn't what it was in the Fifties. Of course, it is a lot less today. But the thing is, before Fantastic Four #1 came out, I doubt that anybody could have sat down and given you an intellectual blow by blow account of what was needed to save the comic book industry. It was just one of those quantum jumps that comes along."

When one looks at what DC was publishing in 1960-1962, it's baffling that anyone would characterize it as "stagnant." If anything, it was Marvel that was stagnant prior to FF #1, not DC. Also, we are supposed to believe two conflicting ideas at the same time: that Marvel doing FF was prompted by DC introducing the Justice League of America in 1960, but that somehow "DC was stagnant" nonetheless. When asked how exactly DC was stagnant, fans will often answer in terms that criticize the comics for not being like what Marvel would become: continuing stories, bickering heroes, etc. This is like criticizing Laurel and Hardy for not being like the Three Stooges, i.e., judging one thing by the standards of some other thing that had its own style and approach.

It's interesting, however, that such fans rarely do the reverse, criticizing Marvel in terms of DC's characteristics, pointing out the lack of imaginary stories or teenage sidekicks as missed opportunities on Marvel's part. Stan Lee claimed to have hated sidekicks (let's ignore Rick Jones for the moment) but many of DC's teenage sidekicks have had long runs in their own titles, as members of long-running group titles, or as backup strips, which indicates that many readers don't share Lee's negative opinion about them. I'm hesitant to deny the "lived experience" of people who were there, but I think that their perception may have been influenced by a naive fandom that was swallowing and regurgitating Lee's biased view of the industry. This isn't to deny the explosion of classic characters that debuted at Marvel between 1961 and 1964, but one ought not to deny the likewise impressive innovations that occurred at DC between, say, 1959 and 1963.

In Origins (pages 71-72), Lee provided a specific example that supposedly set Marvel apart from the competition: "For example, in the early strip [FF#1] we tried to give some dimension to the melancholy Moleman. Remember when he explains how he reached his underground kingdom on Monster Isle -- and why? Didn't you find yourself sympathizing with him, just a bit? There he was, ostracized by his fellow man -- and woman -- because his physical appearance left a little something to be desired. He couldn't find acceptance in our world, so he set out to find another -- one which might have a place for him. Now this was hardly reaching the dramatic heights of a Kafka, but it was almost unheard of in a comic book. Heretofore, villains were villains just because they were villains. Comics merely had good guys and bad guys, and nobody ever bothered with the whys or wherefores. But here, in the first fateful issue of The Fantastic Four, our readers were given a villain with whom they might empathize -- a villain who was driven to what he had done by the slings and arrows of a heartless, heedless humanity. It was a first. It was an attempt to portray a three-dimensional character in a world that had been composed of stereotypes. To comicbookdom, it was tantamount to the invention of the wheel."

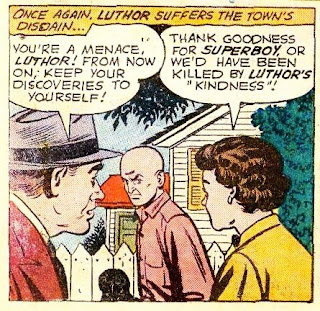

And yet, when Adventure Comics #271 (April 1960) told the origin of Lex Luthor, we learn that he started out as Superboy's biggest fan. It was only after his hair fell out after a lab accident that he blamed Superboy and became his enemy. (You can read the story in full here.) But DC's sympathetic backstory for Luthor is ignored (Lee likely never knew about it) and the credit for "the invention of the wheel" is given to Lee's own work (which came later) by Lee himself. Another example is when fans credit Lee with showing Peter Parker having money problems, claiming this to an unheard-of innovation in comics, when DC's Star Hawkins (who debuted in 1960) also had money problems, regularly forced to pawn his robot companion. But chances are that you've never heard of him.

I think a lot of people believed the things that Lee claimed to have pioneered because many of them didn't know what came before. It's like with Lee's oft-repeated claim in the 1960s that he received as much fan mail as the Beatles; it's a claim that most people accept at face value because contradicting it would involve having information from both sides, weighing the evidence and arriving at an informed conclusion. Sometimes reading Lee's claims about his own achievements makes me wonder if he really knew what he had achieved. Marvel's superhero comics did have merits that other superhero comics of the time did not. The main thing was that there were often consequences to actions in one story which weren't forgotten or ignored in the next. This eventually extended across the entire line. If former villains like Hawkeye and The Black Widow turned into good guys, it wasn't just a trick or a one-story novelty as it likely would have been at DC. There were in fact permanent changes made in DC comics -- for example, the de-aging of Ma and Pa Kent in Superboy #145 (March 1968) -- but a unified continuity across multiple series was less consistently applied (nor would that have been always desirable given DC's variety of styles). Marvel's superhero comics were presented to the reader as meaningful "epics" taking place within a cohesive universe at a time when young audiences were looking for more ambitious (or pretentious) approaches, from pop-music concept albums to paperback book trilogies to cult TV series like Star Trek. Marvel fit in with that overall trend in the late 1960s/early 1970s, at least among those willing to pick up a funnybook.

Early on, DC editor Mort Weisinger rejected the idea of presenting such an ordered universe. In the letters page of Adventure Comics #264 (Sept. 1959), a reader wondered why Aquaman's mother didn't have a fish tail like Lori Lemaris. Weisinger responded, "Are you serious? We publish fiction, not documented history. Different stories present different conditions on different worlds. If not, all stories would be monotonously alike. The Atlantis [that] Aquaman's mother came from has a different set-up than the Atlantis presented in the Superman story. We try to be consistent in our 'ground rules' for each of our characters. For example, Ma and Pa [Kent] own a general store in every issue. It isn't a general store this month and a bowling arena the next. If we show the Green Arrow visiting Mars, it is entirely likely he'll meet inhabitants and creatures different from those encountered by Jimmy Olsen or Batman. If writers didn't use their imagination to vary conditions, all comic book stories and science fiction movies would become so repetitious you'd soon lose interest." Marvel being a smaller company in the 1960s, with only one editor in charge, allowed Lee to satisfy such reader demand for story consistency in a way that DC couldn't or wouldn't do -- at least not until the 1980s when company-wide crossovers (and even encyclopedic character guides) became the norm throughout the industry.

But rather than settle for accepting the plaudits that one has deserved, for many fans (and for Lee himself) credit is given beyond what is justified and in the process claims are made about Marvel's merits that are misleading or provably untrue. For example, back in 2019, a longtime Marvel fan wrote the following on his blog regarding the merits of the "Marvel method" of creating comics compared to the traditional "full script" method employed at DC: "At most other companies the story and dialogue was written and then the comic was drawn. Since the writer could not see the images yet, he had to highlight the description in dialogue. For example, when Superman is jumping out the window the panel would show someone below saying, 'Look, there is Superman jumping out the window.' Or the description would read, 'One day, as Superman jumped out of a window.' Uniquely at Marvel that did not happen."

Let's examine the evidence. To begin with, since no example of a published Superman panel with a caption reading "One day, as Superman jumped out of a window" was shown in the blog post, we can probably assume that the blogger simply invented this for the purposes of providing an example of how such a panel might have appeared. (In other words, he made it up.) Shown below is an actual page from a Marvel comic written by Stan Lee using the "Marvel method": Captain America #100 (April 1968). As you can plainly see, the page does precisely those things that the blogger says that the "Marvel method" prevents (i.e., the words repeating what is already shown in the artwork).

On another Facebook post a while back, former comics editor and writer Danny Fingeroth stated "Without Stan and Marvel's success, unlikely there would have been a Batman show in '66. So maybe comics would just have petered out." This was a strange remark, where even a 1960s DC success in other media is somehow attributed to Marvel, but since I wasn't even alive back then (born in 1970) and Fingeroth (born in 1950) was, I was reluctant to offer a contrary point of view.

The argument is sometimes made that since someone wasn't around (or even alive) reading comics back then, they don't really know what happened. While I can appreciate that sentiment, since I value the recollections of those who were there to witness history being made in real time, there is also an argument to be made that close proximity can distort one's judgment, too. A judgment made from a sentimental or nostalgic perspective may not be as clear and objective as someone coming to it without that emotional bias.

Last year on his podcast, Scott Edelman interviewed comics writer Jo Duffy, and around the 21-minute mark, about Duffy's comics reading preferences growing up, the following exchange occurred (transcript by me):

EDELMAN: So the eternal question that we always ask each other as young fans, Marvel vs. DC, you were on the Marvel side primarily.

DUFFY: Oh, absolutely.

EDELMAN: Yeah.

DUFFY: You know, well, I mean, for one thing -- the Marvel characters seemed to actually be involved in inter-personal relationships with each other. The DC characters, everything was static. I loved it, but every issue you would come into the same status quo, and you would leave and the status quo would not have changed. I mean, occasionally there was a continued story, but things didn't go that far forward. Spider-Man dated Betty, and then, you know, they broke up, and then he graduated from high school and you know....

Once again, "everything was static" at DC according to these Marvel readers, despite the evidence of the comic books themselves. Duffy mentions Peter Parker's graduation from high school, which happened in Amazing Spider-Man #28 (Sept. 1965). However Supergirl (Linda Danvers) graduated high school the previous year in Action Comics #318 (Nov. 1964). So much for "everything" being "static."

DUFFY: I was so excited that every month you felt like a Marvel character could conceivably lose and be heard from no more, and they could lose the people they loved, either to tragedy or to "Well, Peter, you've deceived me for the last time! Whatever's going on here, I don't want to know!" -- hmph, hmph, hmph, flounce, flounce, flounce. So, I was more invested because it wasn't just about fighting bad guys. It's what's going to happen to these people and why are they being so mean.

EDELMAN: There's something additional about being a Marvel fan of a certain age, and you or I are of a similar age, that we were there to see it being born, and coming in to a universe that is totally constructed with all the characters, the whole cast there, all the subplots there, is a heck of a lot different from coming in and saying "Oh, there's Fantastic Four," "Oh now here's Spider-Man," "Oh, now here's the Hulk," or, it's... little by little, and the pieces coming together....

[snip]

EDELMAN: To watch something being born, there's a special thrill that could not occur, could not possibly occur, over at DC which was already constructed, the whole city was built...

DUFFY: You know, what did we get at DC? Go-go checks. We mostly did not get many new characters, or developments that could take the characters completely off the rails.

EDELMAN (sarcastically): Hey, they gave Batman a yellow circle around his bat, how do you like that? I mean, that was... And then they took it away years later [chuckles].

In the podcast, Duffy also talked about Reed and Sue getting married when asked about why she preferred Marvel (which I cut from my transcript above because it went on & on). But the first superhero wedding occurred a year before FF Annual #3 (Oct. 1965) -- in Aquaman #18 (Nov./Dec. 1964). DC's Elongated Man got married earlier, but the marriage ceremony itself wasn't shown on the pages. His honeymoon was depicted in The Flash #119 (March 1961), long before Reed and Sue first appeared in The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961).

As Edelman says above, this material was especially important to readers "of a certain age" -- and it's safe to say that the fans who have the strongest affection/loyalty for 1960s Marvel comics are ones who were born in the 1950s, who were kids in the 1960s as the comics were originally coming out.

If they were ten years old in 1960 (as Fingeroth was) or ten years old in 1965 (as Edelman was) or ten years old in 1964 (as Duffy was), then they were the perfect age to be the most impressed by that brief window of time that saw a parade of new characters coming from the "House of Ideas" and the growth of the characters within the stories at that time.

In 2020, Tom Orzechowski, a well-regarded letterer of Uncanny X-Men in the 1980s, wrote the following on Bob Beerbohm's Facebook wall: "A great many were not reading the comics in 1960, as I was, and were not in a position to perceive, in real time, how the Marvel scripting was more inviting than that at Charlton or at DC. Each person contributed to the best ability. That's the legacy. Marvel was a better read." According to a Google search, Tom was born in 1953, so he would have been 7 years old in 1960. When Kirby left Marvel in 1970, he would have been 17 years old. Obviously he was at the right age at the right time to glom onto the "Marvel Age of Comics." That Marvel was more "inviting," "a better read," is presented as a statement of fact rather than a personal opinion. If you don't understand or agree, then you "were not reading the comics" at the time and not qualified to know or criticize.

Had these fans-turned-pros been born a decade or two earlier, or a decade or two later, their preferences and judgments might be entirely different. To rely, therefore, on the feelings of "those who were there" -- how they felt about the work at the time it came out -- would mean relying on the critical judgment of 10 year olds or, at best, teenagers.

Because Kirby and Ditko were a part of their childhood enthusiasm for Marvel superhero comics in the 1960s, Kirby and Ditko are forever viewed by them through that particular lens. Absent Lee's dialogue and captions, their other work is "missing" something for these readers (the familiar Lee style that they grew up with). Never mind that both men had careers before and apart from their 1960s Marvel work (a fraction of their body of work overall), it is that beloved 1960s Marvel work that is the standard by which all the rest of their work is judged. And the less it is like that work, the less it is loved by them.

One might then conclude that those who grew up reading the stuff might be the least reliable people to evaluate 1960s Marvel comics, since their judgment of them may be colored by memories of their youthful responses to it. But people can change, and I've seen some older readers begin to change their minds about certain comics based on reacquainting themselves with it. Whereas a longtime fan might have turned up his nose at a Lois Lane comic as a teenager, the same fan today might find it charming and refreshing to read -- finally able to see merits in the work that were ignored before.

Because Stan Lee made himself synonymous with Marvel, with "Stan Lee Presents" appearing on their pages long after he was no longer personally involved, brand loyalty by fans to the publisher Marvel is attached to loyalty to Lee as well. But as fans branch out beyond Marvel, and follow creators not publishers, Lee's accomplishments may appear more limited and his claims of originality less credible as one's knowledge of earlier comics grows. Perhaps then a critical assessment of Lee can be made without being called an attack, or a challenge to the conventional wisdom offered without cries that one "wasn't there."

When I wrote my original version of this post on a Facebook group, a poster there offered some pushback to my premise. He wrote: "It may be 'received wisdom' or Stan’s propaganda or whatever, but I get the guy. Marvel’s was a more approachable world, for sure. Saying DC had teenage strips before Marvel, though, is like saying the Sears Catalog had women before Playboy. The Legion or Superboy or whoever made zero attempt to reflect the zeitgeist, ignoring culture to a degree that was off putting, as they did in most of their universe. I’m 62, and I bought into Marvel in the 60s, completely. You can organize historical facts all you like, but the two companies felt different to kids, to me and my friends. Nothing counted in DC books -- no memories, no regrets, no lingering personal issues. 'What if Lois Lane could shit diamonds?' imaginary stories read like exactly what they were -- old, tired admen punching a clock. Not that Marvel was that different in that sense ... but it seemed different to kids at that time, and that difference was real. Maybe it WAS Stan’s phony enthusiasm, but it was real."

In my response, I pointed out that The Legion of Super-Heroes takes place in the 30th century, and Superboy took place in the 1930s, so naturally those two strips weren't going to necessarily comment on what was happening in the 1960s. And yet, even there it can be said that they reflect the times in which they were made. Shown here, for example, is the cover of Superboy #149 (cover-dated July 1968), featuring Bonnie & Clyde. The trend-setting movie based on the famous outlaws had been released in August 1967. When it comes to a DC comic like Batman, it might be said that he WAS the zeitgeist. I recall somewhere someone remarking that the pop culture of the 1960s was the three B's: Beatles, Bond and Batman. I think there is a tendency by many fans to overstate the impact of Marvel on the culture in the 1960s.

Regarding teen heroes, although Bob Haney's Teen Titans is notorious for its poor attempt at hip youth lingo, DC also had the teenage Hawk & Dove who debuted in Showcase #75 (June 1968) and were soon awarded their own series. Surely Hawk & Dove reflected the zeitgeist of the times, if that is the standard by which we are wishing to judge DC's efforts?

As for Marvel being more "approachable," this echoes what Tom Orzechowski was quoted above about them: "the Marvel scripting was more inviting than that at Charlton or at DC." And yet, for many fans (like Barry Pearl, for example, or myself) they read DC before moving on to Marvel. So, for many young readers, it was DC that was more "approachable" because of self-contained stories and more familiar characters (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman). If DC's approach was so "off putting," and that "it seemed different to kids at that time, and that difference was real," then how come DC was selling more than Marvel?

The poster answered that "DC sold more because of distribution, largely," without citing any evidence or data to support this belief. It's a circular argument, in my opinion: DC sold better than Marvel in the 1960s "because of distribution," but when Marvel sold better in the 1970s, "better distribution" is never offered as an explanation. What is interesting is the fact that so many fans "of a certain age" (to quote Edelman) would characterize Marvel favoritism as universal among their age group growing up, despite DC's (and Archie's, for that matter) higher sales in the 1960s. This suggests to me that Marvel fans became more engaged with comics than the readers of other companies, many entering the comics industry professionally and imposing their fannish taste on the comics to come.

Normally, readers would outgrow reading comic books for more substantial literary books, but evidently a large number of Marvel readers stuck with comics (and mainly Marvel comics) long after they would have ordinarily moved on to better things. Perhaps Lee's tongue-in-cheek characterization of his comics as "masterpieces" led to some young readers taking his words to heart, concluding that they need not look elsewhere for genuine literary masterworks and therefore have spent the rest of their lives holding those comics in the highest regard. To suggest that their original youthful assessment could be mistaken is akin to implying that their entire life is a lie, which understandably prompts a spirited defense.

Despite the length of this post, I really don't mind if any of the people I've mentioned above don't like the same comics I do, or have the same opinions as me. A lot of it comes down to personal taste, and we like what we like. And our present views can often be shaped by what we thought of them in our youth, when we read a comic book for the first time. What annoys me is the received opinion of fandom, echoing the self-serving words of Stan Lee, that dismisses the output of other publishers for reasons that are factually unsound. That's what grates.

Part 1

ReplyDeleteFirst things first: Rob and I are friends but we do have different points of view, which we often share with each other. So this is a discussion.

I have read virtually every DC, Marvel, ACG, Warren etc. Action and Adventure comics of the 1960s into the early 1970s. You see, my aunt owned a candy store which was a library to me. So I have read twice as many DCs as Marvels simply because DC published twice as many comics.

While everyone is intitled to their own opinion, they are not entitled to their own facts: Marvel did not and could not outsell DC in the 1960s.

In the 1960s Marvel was distributed by DC’s parent company, National Periodical’s distributer, Independent News. They were limited to 16-19 titles a month. DC published more than twice as many and outsold Marvel, although I am sure a few Marvel titles outsold DC.

In 1969, after Marvel was bought over by Perfect Film, they had their own distributers and began releasing new titles. I have read and collected articles and interviews with Stan Lee and he states that they started outselling DC comic in 1972. Lee used total MONTHLY figures, while Roy Thomas used yearly figures. So when Rob asked, “then how come DC (in the 1960s) was selling more than Marvel?” The simple answer is that DC would not allow Marvel to publish more comics. When they were able to they outsold DC.

This can be confusing. First ADVERTISERS often used yearly or monthly figures, not individual comic sales, to base their rates. Second (and this can be a bit confusing) circulation can be judged differently. If Spider-man sells 300,000 copies a month, it could be considered a better seller than Justice League that sells 350,000 a month. How? Spider-Man was monthly, selling 3,600,000 a year while the JLA is published 8 times a year for a total of 2,800,000. That difference means a great deal to advertisers.

So Marvel, in 1972 exceeded DC’s totals not just because the price was different, but because, for the first time, they were able to put out a lot more titles. And, of course, many buys switched from DC to Marvel because they liked Marvel more. It was not just that nickel difference.

Part 2

ReplyDeleteRob quotes Stan, "As each succeeding issue of The Fantastic Four increased in sales and in popularity” and then writes, “such a sentence is not meant to be taken seriously.” Why not, it’s accurate. The Fantastic Four was a success and sold better each month.

Rob continues…”many young fans became "faithful" Marvelites, urged on by Lee's partisan cheerleading, … helping to promulgate the notion of 1960s Marvel as the gold standard in comics.” The Marvel readers were not brainwashed robots, they were people with their own preferences.

Frankly, I read and then collected Marvels because I liked them, as I grew older, Marvel was growing with me, not DC. Yes, I felt that Marvels were better, but I felt that way because of the stories, the writing and the art, not because Stan told me. DC also had a lot of gimmicks that I tired of. The cover would show Superman getting old, losing hi hair, getting fat, losing his powers, dying, being tortured by a friend or killing someone. It was often a mistake, a dream, an imaginary story, a practical joke…. A gimmick. How much of that can you read?

I spoke to Julius Schwartz and Carmine Infantino about this. They claimed that their comics were aimed at the twelve- to fifteen-year-old. When they got older than that the lost them. So their DC plots were often simpler, their dialogue was more elementary and they had very little character development because fans would leave quickly. Marvel did aim at an older audience and used more advanced vocabulary and longer stories. Stan was aiming at college age readers too.

When I was young, and not identifying artists yet, the DC artists seemed to have the same style. For example, all the artwork in the Superman family, (Lois Lane, Jimmy Olsen, Action, Adventure etc) seemed to look alike (except for Wayne Boring). In fact, when Jack Kirby drew in Jimmy Olsen they redrew his faces.

Jack Kirby was the “house” artist for Marvel and he was very different from the artists at DC. Jack’s work always showed motion and emotion, while at DC the characters often looked posed.

I enjoyed Gil Kane on Green Lantern for many years. But he seemed to develop more, and was given more freedom, when he got to Marvel. I loved his work, such as Warlock, with Roy Thomas. And his Spider-Man. He told better and longer stories at Marvel. Johnny Romita did love stories, mostly, at DC. His work on Spidey was outstanding and made the comic Marvel’s best seller. And there was a difference in impact between Romita and Swan in the covers you showed. Romita came first and was original.

That’s an important point. The Marvel artists were not married to a house style like they were a DC, although, to be fully honest, many emulated Jack Kirby when they could.

Rob wrote: "DC published more teenage-age superhero characters than Marvel ever did in the 1960s and 1970s." Now I am mostly talking about the 1960s and early 1970s here. DC, with the Legion, was the first to have stories about teenagers. Sadly, most of DC teens, Robin, Speedy, Aqualad, etc had the worst job in comics: They were sidekicks. As sidekicks, they were always in danger, always being rescued, often saying used as humorous relief, and frankly did not have a teen age life…or any friends. They were never very developed. (Neither were Toro or Bucky in their Marvel days.) The Legion of SDuper-heroes had a unreal and unrelatable life. There were no adults or parents around, nothing about schools, nothing readers could relate to. Rob would later dispute Stan’s claim that Goodman thought that teen-agers could only be sidekicks by pointing out Superboy. Superboy was an exception and was another version of Superman. Goodman, who had experience publishing comics, stated a valid opinion. Goodman, was a successful publisher, and does not come out looking like a “dope” but someone who did misread the tealeaves.

ReplyDeleteBut Marvel readers related to Peter Parker, Johnny Storm and the X-Men. They had lives….they dated, went to school, they failed at times and need to get jobs. Money was an issue here. Also permanence. That is, a disaster would happened to young Clark Kent. It would last only an issue. His farm would burn down, for example. Yet by the next issue it was restored. Peter Parker would be poor for a long time.

There is a relentless premise here that somehow Stan ha this incredible influence on kids and was brainwashing them. This is silly. And there are some things about comic buying in the south that Rob does not know, but I do because I lived in the south during the Senate Hearing and the comics code. Rob writes, “ a "letter from 'John Doe' supposedly an anonymous 16-year old from Texas [who] asks if he broke the law by buying the book. This may be a planted letter by Lee..." No, Stan knew this and I saw this. After the Senate hearing, comics, in southern stores, were removed from the front of many stores and placed in a back room where only “adult” material was sold.

Part 4

ReplyDeleteAnd comics were suffering and stagnant in the early 1960s. On Sept 23, 1962, the New York Times ran a long a serious article on the state of DC as readership was shrinking…”National Periodical, Superman’s publisher, presently derives only about $176,000 a year from advertising, compared with nearly $1,000,000. a decade or so ago.” But even Mort Weisinger admits his readership is changing.. “The kids still love this sort of stuff,”Mr. Weisinger affirms. “But in putting together the book we have to bear in mind that the kids today are much more sophisticated than they were twenty years ago. There are a lot of things.”

Marvel through the early 1970s was able to established a continuity not seen at DC. Stan was the only editor at first and wrote most of the stories. He dealt with a handful of artists. Later he was joined by Roy Thomas who was also big on continuity. Not only did DC have many editors and writers, their super-heroes always appeared in at least two comics, making continuity and character growth almost impossible. In the mid 1970s Marvel too began having multiple comics for each character and character progression halted.

I won’t continue A major theme here is to criticizes Stan, who was a successful businessman, who promoted his projects. It also criticizes the Marvel fans who did not like DC. (and credits Stan for their not liking DC.) The promotion that DC had is not mentioned here. The piece also singles out exceptions, rather than the rules.

Simply, while DC introduced me to super-hero comics, before Marvel had theirs. I felt in the 1960s Marvel staff, Lee, Kirby, Ditko, Romita, Thomas, Steranko, J. Buscema, et all produced some of the best comics I ever read.

It is a pleasure to discuss this with Rob Imes.

ReplyDeleteFirst we should have mentioned that Dell/Western and Archie were best sellers. In fact, Archie is one of the three companies that have survived since the 1930s.

But first, just because a comic is more popular than another, it does not make it better. There are too many books, TV shows and movies that did not achieve the popularity of some lesser efforts.

Rob, I have given up on the use of the words “best” and “better.” We can argue that forever. I do use the word “FAVORITE,” what comics I like the most. I do see a great difference between Marvel and DC and do have a strong preference. You feel differently, that’s okay.

About Marvel advancing in sales you wrote: “when Marvel sold better in the 1970s, "better distribution" is never offered as an explanation."” Here I disagree with you. Marvel now had its own distribution company for the first time since 1958, as did DC. So, for me it was now an equal race, with both parties beginning at same starting line.

I do not have the full facts about sales figures you mention from Comichron. But as I mentioned before a Spider-Man title, with 13 issues (annuals included) may have sold less per issue, but more yearly than a bi-monthly. And I really don’t know how accurate those postal reports are. But it proves a point. Superboy, per issue, outsold Spider-Man. But yearly sales for Superboy would be (roughly) 3,720,000 and Spider-Man 4,464,000.

But we don’t know who was buying he comics. I believe that Marvel tilted towards an older audience. In the era we are discussing, I thought Stan was a good writer and a funny personality. I did NOT read his comics because he said so, but because I liked the comics. And I didn’t not take his “mankind” statements seriously.

Rob, this is very serious. Beerbohm insults people who like Marvel by calling them (and me) names such as Marvel Zombies. He trashes Stan and all things Marvel.

You look at the beginning of the Silver Age at DC differently than I do. For me this was a revival era, not a new one. The Flash, Green Lantern, JLA were versions of what was created in the 1940s. The Marvel Era seemed new. Yes, it had the Torch, Cap and Subby, but Lee, Kirby and Ditko gave us brand new characters. You mention Superboy. Often, as with the Lex Luthor story, Superboy just retold stories and introduced characters that appeared in Superman, a decade earlier.

Lee may not have pioneered all that he claimed, but we look at the world by who was first successful. For example, Dr. Droom was Marvel first super-hero, but we say it was the Fantastic Four. You point to Star Hawkins, but, you are right, who ever heard of him?

You don’t mention what Stan brought to comics in his writings. He brought INDIVIDUALITY, the characters had their own PERSONALITIES and didn't sound alike; INTIMACY, characters used their real names and had romances too; Humor; a grater VOCABULARY and he developed the Marvel Method so that artists had input in the scripts.

You keep mentioning, many times, Stan’s promotions as bad things but Roy Thomas said when he became editor that he wasn’t hired to great great comics but to sell them. Stan did both.

Thanks to Barry Pearl for the long and thoughtful reply! I should say up front that my blog post focused on the superhero genre and on DC because that was the focus of the opinions I encountered. For example, the poster on Bob Beerbohm's page was focusing on Marvel superheroes compared to DC superheroes, not other genres nor other publishers, so that is why I focused on those things in my response. I could have pointed out that Archie and Gold Key had titles that sold more issues than Marvel titles in the 1960s. Sales information for that decade can be found at https://www.comichron.com/yearlycomicssales.html

ReplyDeleteWhen it comes to sales, my understanding is that there was not a big difference between annual sales of a series and monthly sales of a series. At least it appears that way when looking at the Statement of Ownership boxes in the comics, which usually list the annual circulation of a series as well as the circulation closest to the month that the info is being filled out. Advertisers generally purchased ads for an entire month across an entire line (there were exceptions like for the romance lines), not picking and choosing which series that they wanted their ad to appear in, so perhaps this means that they are judging by overall annual company sales rather than an individual series' annual sales (which are the numbers that the Comichon site lists). Marvel more often allowed small ads and classifieds from comic book dealers than DC did, but I don't know if that is because they were not receiving enough interest for ads from larger companies. (DC also ran PSAs, unlike Marvel.) Someone like Bob Beerbohm would know more about the advertiser situation than I ever would.

Anyway, that wasn't the main thrust of my blog post. The main point was that there are claims made about why Marvel superhero comics were better than DC superhero comics in the 1960s & 1970s by citing reasons that can be shown to be not unique to Marvel (and thus throwing into question why they are being cited as reasons).

ReplyDeleteBarry wrote, "Marvel did not and could not outsell DC in the 1960s" because DC made more titles than Marvel did. True, if one is counting overall sales for the entire company. But limiting the number of titles that one can distribute does not explain why individual titles sell the way that they do. The Hollywood Reporter article I quoted said Marvel "began outselling DC in the mid-1960s." Is that a true statement or a myth based on fan perception? According to what you have written above ("Marvel did not and could not") it sounds like we agree, that the popular idea that Marvel was outselling DC in the 1960s is false.

Barry wrote, "So Marvel, in 1972 exceeded DC’s totals not just because the price was different, but because, for the first time, they were able to put out a lot more titles. And, of course, many buys [buyers?] switched from DC to Marvel because they liked Marvel more. It was not just that nickel difference." This is an example of the kind of thinking I objected to in my blog post: "It's a circular argument, in my opinion: DC sold better than Marvel in the 1960s "because of distribution," but when Marvel sold better in the 1970s, "better distribution" is never offered as an explanation."

Perhaps I should have said "rarely" rather than "never," since you do say that Marvel being able to put out more titles in 1972 (which we can call more exposure, or better distribution terms if not better distribution) caused them to overtake Marvel in sales. But if the answer is also "because they [readers] liked Marvel more," then why is that also not an explanation for why individual DC series sold better than individual Marvel series in the 1960s? The Comichron site says of the year 1969: " Amazing Spider-Man sales were nearly flat, but in this market that still allowed it to reach the Top 10 for the first time." ASM was #7 on the chart that year, being outsold by Superboy (#3) and Lois Lane (#4). Did more readers like Superboy than Spider-Man in 1969? That's what the sales numbers would seem to suggest. And that fact flies in the face of fan perception about the value of those DC titles. Eventually this perception becomes accepted fact, even when flawed or mistaken according to the data.

I should add here (as I did in my blog post) that Marvel's sales did increase throughout the 1960s. They were becoming more popular with readers than they were at the beginning of the decade. Marvel was having an impact on the creative choices at DC, too, during that time. For example, Jim Shooter has talked about being a Marvel fan as a teenager and wanting DC to be as exciting as Marvel. When he began writing for the Legion series in Adventure Comics, he introduced the Karate Kid specifically to add more physical action to the series. Marvel tended to have more exciting fight scenes than DC did (especially with Kirby being the guide to other artists at Marvel about how the pages ought to look). I probably should have mentioned the higher degree of action/fights in Marvel superhero comics in the section of my blog post where I wrote "Marvel's superhero comics did have merits that other superhero comics of the time did not." This could explain why some fans (like the poster on Bob Beerbohm's page) thought that Marvel had better artists than DC, even when they had some of the same artists at various times.

Barry wrote, "Rob quotes Stan, "As each succeeding issue of The Fantastic Four increased in sales and in popularity” and then writes, “such a sentence is not meant to be taken seriously.” Why not, it’s accurate. The Fantastic Four was a success and sold better each month." No argument from me there. What I was saying ought not to be taken seriously was Lee's exaggeration about the extent of the FF's sales and popularity, when he added "a breathlessly waiting mankind the indescribable pleasure of another mighty Marvel superhero." Mankind, in general, did not care. There's an interview with Lee from the mid-1970s on YouTube where he talks about the success and popularity of the FF, and the interviewer confesses to having never heard of them.

ReplyDeleteBarry wrote, "I spoke to Julius Schwartz and Carmine Infantino about this. They claimed that their comics were aimed at the twelve- to fifteen-year-old. When they got older than that the lost them. So their DC plots were often simpler, their dialogue was more elementary and they had very little character development because fans would leave quickly. Marvel did aim at an older audience and used more advanced vocabulary and longer stories. Stan was aiming at college age readers too."

Even when I was a teenager in the 1980s, the majority of comics readers were teenagers or younger.

I wrote the following post last year on my FB wall: "In DC COMICS PRESENTS #94 (June 1986), a 17 year old reader wrote in complaining that there was too many 'good guy vs. bad guy' plots in comics and called for more realism to appeal to older readers like himself. DC Production Manager Bob Rozakis' wife Laurie occasionally answered the letters in the Julius Schwartz-edited titles in the mid-1980s, and she explained to the reader that he was probably outgrowing most superhero comics and was hopefully reading other stuff. Sounds logical to me, but I can only imagine how some hardcore comics fans who take superheroes seriously as adult literature may have reacted to that response."

She had written (in part): "Sounds to me like you're outgrowing some of the comic books you've been reading and should be moving on to other things. ... Face it, comic books are aimed at a younger audience for the most part. A few are written with more mature readers in mind.... and there's no reason why you can't still enjoy them, but there's a lot more to be read in this world. You aren't the first comic book reader to go through this stage.... it's part of growing up."

On May 17, 2021, I wrote a post on my blog titled "The Aging Demographic of Comic Book Readers" where I showed the results of some age surveys about comics and science fiction fans through the years. In 1985, the Comics Buyer's Guide ran a survey that received nearly 6,000 votes. It found that "The most common age was 14 years; the age with an equal number above and below it was 17, and the arithmetical average age was 19.3." Only 36 voters were over the age of 40. But the largest number (646 voters) were 14 years old -- the same age that I was at the time. Presumably the numbers skewed even younger in previous years.

While Lee gave lip-service to aiming at an older, college-age audience, I think that Marvel's focus on superhero comics casts doubt on that aim. For Marvel to have truly aimed at an older audience in the 1960s and 1970s, the results would have looked more like their B&W magazines (and later, Epic Illustrated) than the four-color superhero comics they produced. The undergrounds of that period were aiming at the audience that Lee claimed to be aiming for, and yet when given the chance to do something similar with "Comix Book," he was uncomfortable and pulled the plug.

ReplyDeleteBarry wrote, "So their DC plots were often simpler, their dialogue was more elementary and they had very little character development because fans would leave quickly. Marvel did aim at an older audience and used more advanced vocabulary and longer stories." Although DC had more backup stories than Marvel (for greater variety, in my opinion), they also had some longer stories. For example, the first full-length Barry Allen "Flash" story was in THE FLASH #120 (May 1961) -- which is before Marvel's superheroes were introduced. The first Earth-Two story was in #123 (Sept. 1961) which allowed for more complexity as well as more imaginative possibilities, and demonstrating an interest in responding to older fans' nostalgia by reviving the Golden-Age Flash.

Personally I did not think that DC's plots were simpler than Marvel's (which relied more on fight scenes than DC did) or that they used fewer big words. Some of the writers for DC's superhero comics were professional novelists like Gardner Fox, Edmond Hamilton and Otto Binder. Certainly they had more experience writing prose than Stan Lee or Roy Thomas ever did.

Barry wrote, "And there was a difference in impact between Romita and Swan in the covers you showed. Romita came first and was original." As I wrote in the post: "You can compare the two artists right here. The Amazing Spider-Man cover shown above is #87 from 1970, drawn by Romita. The Superman cover is #201 from 1967, penciled by Swan and inked by George Klein." Since 1967 comes before 1970, that means the Swan cover was done first, not the Romita cover. The "Romita came first and was original" comment makes no sense to me. Can you explain what you meant?

Barry wrote, "Sadly, most of DC teens, Robin, Speedy, Aqualad, etc had the worst job in comics: They were sidekicks. As sidekicks, they were always in danger, always being rescued, often saying used as humorous relief, and frankly did not have a teen age life…or any friends." They began as sidekicks, but many of them soon graduated to their own backup stories. (Robin first had his own solo series in the 1940s, in fact.) Kid Flash's first solo story appeared as a backup in THE FLASH #111 (Feb./March 1960). Aqualad (and the JLA incidentally) were introduced the same month. Kid Flash got a costume change in #135 (March 1963), becoming a bit more his own man (boy) since his previous outfit was identical to his mentor's. Things continued to progress when the Teen Titans was formed. (Robin eventually went off to college in 1969 (Batman #217). No one was rescuing these sidekicks in their solo or team books; the kids were on their own. Characters like Dick Grayson and Wally West continue to have a devoted fanbase to this day, but they wouldn't exist if there had been a ban on sidekicks at DC. Perhaps Marvel eventually recognized the value of sidekicks when Bucky Barnes was revived as the Winter Soldier in 2005, eventually getting his own monthly series in 2012 (which I had on my pull list for awhile).

Barry wrote, "Also permanence. That is, a disaster would happened to young Clark Kent. It would last only an issue. His farm would burn down, for example. Yet by the next issue it was restored." There were also inconsistencies in Marvel comics, when things were forgotten, plot developments abandoned. In Avengers #35 (Dec. 1966), for example, Captain America's shield was destroyed, only to be back on his arm without explanation later that same issue. But as I noted in the blog, although DC had less adherence to continuity than Marvel, there were still changes that happened to the characters, such as Linda Danvers graduating high school and going to college. Such changes in direction were not undone or forgotten the next issue.

ReplyDeleteBarry writes, "Rob writes, “a "letter from 'John Doe' supposedly an anonymous 16-year old from Texas [who] asks if he broke the law by buying the book. This may be a planted letter by Lee..." No, Stan knew this and I saw this. After the Senate hearing, comics, in southern stores, were removed from the front of many stores and placed in a back room where only “adult” material was sold."

I was quoting the GCD entry for that issue, which said that "This may be a planted letter by Lee." However, I have no reason to doubt it given the letter by his wife (or, at least, using her name) in the next issue. The letter pages in AAF were short and sparse to begin with, but gradually got more mail the longer the series ran (which wasn't long, which suggests that the increased mail wasn't necessarily helping sales).

Barry wrote, "Not only did DC have many editors and writers, their super-heroes always appeared in at least two comics, making continuity and character growth almost impossible." On the other hand, the titles that Mort Weisinger edited seemed to feed off each other, so that if a character or concept was introduced in one series, it would eventually find its way into the other series. Bizarro, for example, debuted in Superboy #68 (Oct. 1958) but soon was appearing in Action Comics the following year, and then had his own backup strip in Adventure Comics. The introduction of the Legion and Supergirl around the same time similarly impacted other Weisinger-edited titles.

Anyway, that's it for now.... Thanks again for the long reply and your feedback on the post.

Rob:

ReplyDeleteHere is the difference between us:

Simply I lived through the Stan Lee Era of the Marvel Age, 1960-1972 and you didn’t. You mentioned Stan about 25 times in your post and I thought that was the era we were discussing.

I read 25-30 DC comics a month for much of that time. And I read 10 Marvel comics, along with a host of others, all at my aunt’s candy store. Having not been there, you pick and choose a comic or two that supports your ideas. Or you rely on others, such as Beerbohm for information, which is their perspective. Your comment of Stan planting a letter comes from the GCB, not you, you weren’t there.Yet you make it your own when you include it.

Robin is a great example. For the decades of the 1950s and 1960s he was a sidekick with all those features I mentioned. You select a comic, from 1969, that changes things. But it did not change it retroactively, he was a sidekick for most of the era that I read comics.. (I fall off the DC reading after about 1970 and off all comics by 1976.)

Stan gave a personal touch, which you seem to feel was just salesmanship, but invited us into Marvel. Letters were opened with “Dear Stan and Jack,” for example, not an unknown “Dear Editor.” Stan added humor, which other editors didn’t. As for reaching older readers, Marvel comics were ion sale at colleges, my colleges, in the early 1970s, DC weren’t. And Stan made dozens of appearances at colleges (and got paid very well for that). DC editors were not invited. You were not there at this time, I was, so you didn't see it.

You don’t point out DC’s promotion. I belong ed to the “Superman of America” club with its secret code every month. All the codes just promoted DC comics. All DC adds said their comics were great. Yeah, Stan was an over the top salesman, but Marvel was a “minority” company by then.

The Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, Avengers, X-Men, Daredevil and Sgt Fury comics were all full length, allowing for story and character development. The “Double Star Issues” did not have five-page fillers, but 10 to 12 page stories that were most often continued allowing for the aforementioned development. Frankly, you often point out the exception, not the usual, as with “the great “Flash of Two Worlds.” DC mostly didn’t do that. I loved some of their occasional full-length stories. But they were the exception, not the rule.

By looking back, as you do, from the 1980s you can spot exceptions to everything, both pro and con. But I am not just discussing the Superman or Batman family, but Sea Devils, I Spy, House of Secrets, and Aquaman. Marvel’s Tales to Astonish, Strange Tales, and yes, the Amazing Adventures with stories that did not insult your intelligence, was far different than DC’s House of Mystery. Frankly they were often creepier. Ditko gave mood and atmosphere, the storis were darker and mor surprising. Marvel’s war stories developed characters and even had their REGULAR characters die. I loved DC I-Spy, but it did not compare to SHIELD by Kirby or Jim Steranko.

Marvel’s world also looked more like mine, DC didn’t. DC had virtually no black characters and the heroes all existed in imaginary cities. Marvel had black characters and they all lived in my city, New York.

You mentioned to me how you got a bunch of Superboy (I think) comics when you were 14 and loved them. Well, at age 14 you should. Having lived through that era, I got them when they came out at ages 12, 13, 14…17. 18…19 etc and their charm wore off as I got older.

What I can’t do, what you can’t do, is go back in Dr. Doom’s Time Machine and show what comics were like in the 1960s and how Marvel changed them over the decade. You come from a much later time, when comics already have changed and don’t see a major difference. You site exceptions as if they were the rule, I lived through the entire package.